INTRODUCTION

.ref-quote-container { position: relative; background: #1b3a60; width: 350px; float: right; margin: 4px; } /* Slides */ .ref-quote-container .refSlide { display: block; padding: 15px 30px 15px 30px; text-align: center; } .ref-quote-container q {} .ref-quote-container .ref { /* font-style: italic; */ color: #ffffff; margin-top: 10px; text-align: left; line-height: 1.3; }

This report was made possible through funding from IIE’s Fulbright Legacy Fund.

Prepared by Evgenia Valuy

Research, Evaluation and Learning Unit, IIE

U.S. FULBRIGHT SCHOLAR PROGRAM

The Fulbright Program is the flagship international educational exchange program sponsored by the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs (ECA).

The goals of the Fulbright Scholar Program are to (1) strengthen bilateral ties by demonstrating the cultural and educational interests, developments, and achievements of the people of the United States and other nations and (2) promote international cooperation around educational and cultural advancement.

IMPACT SURVEY OF U.S. SCHOLARS (2005 – 2015)

The purpose of this historic report is to present findings on the medium- and long-term impacts of the Fulbright Program related to knowledge sharing, mutual understanding, changes at the organizational, community, and societal levels. The report speaks to the Fulbright knowledge footprint of Fulbright scholars and how their Fulbright grant affected their work and the impact on others.

In June-July 2018, IIE administered an impact survey to Fulbright U.S. Scholar Program alumni who completed their program between 2005 and 2015. The survey was sent to 7858 scholars with updated contact information. This report analyzes responses of 3142 scholars. The response rate for the survey was 40%. All quotes in the report use the original style of the respondent unless noted otherwise. Throughout the report, we use alumni, scholars, and respondents interchangeably. The findings are representative of all respondents, unless disaggregated by any criteria. Graphics in the report highlight a specific finding and do not include all data points.

Limitations

Historic Records of U.S. Scholar Alumni. IIE used historic program data to identify alumni records of U.S. Scholars who participated in the Fulbright Program in 2005 – 2015. While the program had some updated records for Alumni, a limitation of our analysis is that some email addresses were outdated.

Self-selection of Alumni. Alumni answered the survey voluntarily; as a result, our analysis is prone to respondent bias. Scholars may have had positive or negative reasons for completing the survey. The analysis that follows reflects the respondent population only and cannot be applied to all program participants.

- SURVEY POPULATION

-

This section describes the scholars who completed the survey. Where historic demographic data for the overall U.S. Scholar program population during these years was available, the evaluation team compared that data to the final survey population to assess the representativeness of the survey respondents.

SCHOLAR DEMOGRAPHICS

Male respondents constituted 56% of survey respondents and female respondents were 44%. At the time of the survey, the age of respondents ranged from 30 to 94 years, with an average scholar being 60 years old. At the time of the program, an average scholar who responded to the survey was 51 years old. Gender proportion and average age of the survey respondents is consistent with the gender proportion and average age of the overall U.S. Scholar program population during 2005-2015.

While all respondents were U.S. citizens, 3% or 84 respondents were born outside of the U.S. 59 respondents (2%) chose their birth country as their host country for the Fulbright grant; 4 of them are still residing in that country after their grant completion. At the time of the survey, 96% of the scholars lived in the U.S.

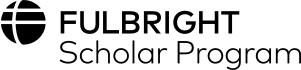

32% of respondents self-identified as minorities or members of underserved communities in the U.S. The proportion of scholars who self-identified as a racial or ethnic minority varied by the age of the scholar, not by program year. This finding is consistent with the consistency of minority racial and ethnic representation in the U.S. Scholar program between 2005-2015, indicating that the racial composition of the U.S. Fulbright Scholar program has been consistent over time.

SCHOLARS’ GRANTS

93% of respondents represented the core U.S. Scholar Fulbright Program. 5% of respondents participated in the International Education Administrators Seminars, and 2% had Global Scholar Awards, NEXUS or Arctic Initiative grants. 43% of respondents had teaching & research grants, 30% had research grants only, and the remaining 27% had teaching grants.

More than half of the respondents (59%) had one-semester grants that lasted between 2 and 6 months. A third of respondents (35%) had grants longer than 6 months. Survey respondents equally represented all cohorts between 2005 and 2015.

The number of years since the Fulbright program completion was one of the most important factors in the scholars’ ability to achieve institutional-level outcomes, which underscores the fact that institutional changes take a long time to be achieved.

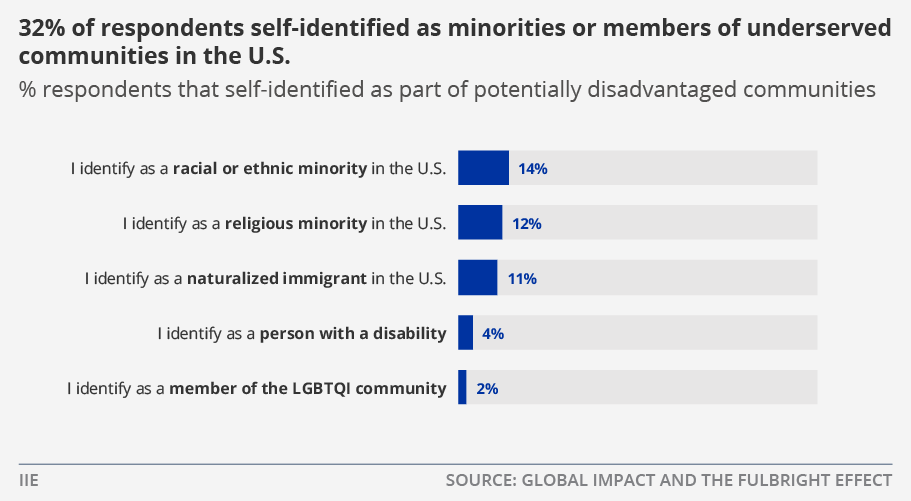

The number of years since the Fulbright program completion was one of the most important factors in the scholars’ ability to achieve institutional-level outcomes, which underscores the fact that institutional changes take a long time to be achieved.Almost half of scholars (45%) went to host countries in Europe and Eurasia; 17% of these Scholars went to Germany. Of the 17% of scholars who went to host countries in East Asia – Pacific, 21% of scholars went to China and 20% went to Japan. Western Hemisphere was the third most popular host region among scholars; this region had equal numbers of scholars pursuing grants in Brazil, Canada, Chile, and Mexico.

IIE used the demographic and program characteristics of survey respondents to identify any contextual nuances in the survey findings that follow. The findings chapters present outcomes related to the professional growth, behavioral changes, and professional exchanges of U.S. Scholar alumni. Further, the report focuses on institution-level analyses and community analyses of U.S. Scholars.

- PROFESSIONAL PATHWAYS

-

Participation in the U.S. Fulbright Scholar program affected the scholars’ careers in multiple ways, such as enhancing their existing positions and leading to new leadership opportunities. For some scholars it also resulted in significant changes to their professional trajectories.

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

At the time of the survey, the majority of scholars (82%) were employed; of these, 92% worked in higher education. 86% of scholars who worked in colleges and universities were faculty: of these, 89% were tenured or on tenure track. An additional 11% of scholars served as emeritus professors, and 5% were retired.

The majority of scholars (96%) were residing in the U.S. Of the scholars that are currently abroad, 47 scholars (1.5%) had moved to their host countries.

.single-quote-container { position: relative; background: #f4f4f4; } /* Slides */ .single-quote-container .mySlides { display: block; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .single-quote-container q {} .single-quote-container .author { font-style: italic; color: #7f8c8d; margin-top: 10px; }Fulbright gave me two grants, one to the University of Tokyo in 1999 and the second to St Petersburg State University in 2004. I used the second grant to make an opportunity to retire in Illinois, and I moved to St Petersburg. I now teach again at St Petersburg State University which was my host during my Fulbright grant.- Alumnus, Russia, 2005

PROFESSIONAL PATHWAYS

40% of scholars noted that the Fulbright program had a profound impact on their professional advancement.

Reputation

95% of scholars experienced increased respect from others in their professional life and noted a positive impact of the Fulbright Program on their professional reputation as a result of their participation in the Fulbright Program. This impact was greater for younger scholars who were still establishing themselves in the field due to their age.

.slideshow-container { position: relative; background: #f4f4f4; } /* Slides */ .mySlides { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } /* Next & previous buttons */ .prev, .next { cursor: pointer; position: absolute; top: 50%; width: auto; margin-top: -50px; padding: 16px; color: #888; font-weight: bold; font-size: 20px; border-radius: 0 3px 3px 0; user-select: none; } /* Position the "next button" to the right */ .next { position: absolute; right: 0; border-radius: 3px 0 0 3px; } /* On hover, add a black background color with a little bit see-through */ .prev:hover, .next:hover { background-color: rgba(165, 165, 165, 0.4); color: white; } /* The dot/bullet/indicator container */ .dot-container { text-align: center; padding: 10px; background: #a5a5a5; } /* The dots/bullets/indicators */ .dot { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; } q { /* color: #1b3a60; */ } /* Add a blue color to the author */ .author { font-style: italic; color: #7f8c8d; margin-top: 10px; }I returned much more fluent in the target language and more familiar with new research materials. This affected my interactions with students and scholars. It added "authenticity" to my role as a teacher and scholar in my field.- Alumnus, China, 2011

Being that I was able to complete a book from my Fulbright grant experience and I am a worldwide expert in my field, this only enhanced my credibility and in turn was a major benefit to my home institution. Being a Fulbright scholar is always something that my institution champions and uses to their benefit.- Alumnus, Germany, 2015

I believe I would not have been hired if not for my Fulbright. I'm the first and only American Indian professor at the district, and the only one teaching American Indian history.❮❯- Alumnus, Indonesia, 2009

var slideIndex = 1; showSlides(slideIndex); function plusSlides(n) { showSlides(slideIndex += n); } function currentSlide(n) { showSlides(slideIndex = n); } function showSlides(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote .mySlides"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote .dot"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex - 1].className += " active"; }Awards

Participation in the Fulbright program led to further grants, including other Fulbright grants, and recognition through various awards.

I was able to do advocacy for the Roma of Romania and also for the artists of Romania. During my appointment I worked with several advocacy organizations as well as my host institution. Since my appointment I have been able to connect these organizations and was successful in receiving an Andy Warhol Foundation grant in order to host exhibitions about Roma and Romanian arts and civil rights. I received a Tanne Foundation award for humanistic socially engage art.- Alumna, Romania, 2014

Leadership Roles

78% of scholars felt that they increased their leadership skills during their Fulbright grant. Combined with increased respect, this resulted in more responsible and leadership-oriented roles and promotions for 58% of scholars. Changes related to leadership roles were more likely to occur for younger scholars; perhaps because older scholars may have already held positions of high leadership.

.mySlides2 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot2 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot2:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }My Fulbright experience motivated me to take a leadership role in our local elementary education system. Shortly after the completion of my grant, I accepted a position on the school board. The understanding I gained during my Fulbright grant helped me to engage board members with an open mind, to respect their diverse perspectives/opinions, and to work as a team.- Alumnus, Greece, 2013

My first Fulbright (U.K.) led to some op-ed articles and a book (reviewed in the mainstream press) on important public-policy issues. It also involved work in theater that led to a part-time career as a theater director at theaters in the US. My second Fulbright (Bulgaria) led to a second book, also noticed in mainstream publications, and my third (Czech Republic) led to a full-time professorship and directorship of a student theater company in the host country.❮❯- Alumnus, Czech Republic, 2013

var slideIndex2 = 1; showSlides2(slideIndex2); function plusSlides2(n) { showSlides2(slideIndex2 += n); } function currentSlide2(n) { showSlides2(slideIndex2 = n); } function showSlides2(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote2 .mySlides2"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote2 .dot2"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex2 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex2 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex2 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex2 - 1].className += " active"; }New Professional Trajectories

For some scholars the Fulbright grant led to changes in their professional careers. As a result of their participation in Fulbright, some scholars rethought their professional interests in favor or against academic careers, while several scholars had to search for new employment because the previous was discontinued. All of these scholars commented on the value of the experience to their decisions.

.mySlides3 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot3 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot3:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }Before Fulbright, I wasn't sure I wanted to teach at the university level. After Fulbright, especially conducting presentations via small in-country grants, I decided to pursue a career in higher education. I am now an Assistant Professor. I credit my time as a Fulbright Scholar-I gained valuable higher education experience.- Alumna, Ethiopia, 2014

My Fulbright experience caused me to change my profession. I never returned to my home community or my home institution. I am no longer focused on research and academic issues, although I occasionally lecture at universities and edit and review articles. Mostly I am engaged in building civil society institutions.- Alumnus, Bangladesh, 2007

Truthfully, I lost my job because I took the Fulbright and my employer "eliminated my position," if you can believe that! But, if I could do it all again, I certainly would! I currently teach in a high-needs school and many of my students come from the regions where I was for my grant - the Caribbean. I can use my cultural knowledge daily to help to understand where my students come from.- Alumna, Barbados, 2010

Partly because of my IEA Fulbright experience, I made the decision to pursue a new Ph.D. in Higher Education Leadership.❮❯- Alumnus, South Korea, 2015

var slideIndex3 = 1; showSlides3(slideIndex3); function plusSlides3(n) { showSlides3(slideIndex3 += n); } function currentSlide3(n) { showSlides3(slideIndex3 = n); } function showSlides3(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote3 .mySlides3"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote3 .dot3"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex3 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex3 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex3 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex3 - 1].className += " active"; }462 scholars (15%) established new organizations; some organizations were directly related to or located in their host countries.

.mySlides4 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot4 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot4:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }I have continued my artistic collaborations over the past 7-8 years since my Fulbright. The first was to remain in the host country as an art teacher at a school, then return to India every year for 6 weeks - 2 months of the year. I started a textile company as a direct result of my research, and teach workshops all across the country.- Alumna, India, 2011

After my Fulbright I cofounded Alliance for Innovation a nonprofit that is building bridges between Poland and the U.S.- Alumnus, Poland, 2011

Because of my experiences in the Philippines, I founded NEW Pathways to Enterprise, a 501c3 organization that works in the Philippines to enable women in poor communities to start small businesses so that they can achieve their dreams of a better life for their families. Nearly 400 women have completed our Learning to Livelihood program in the Philippines since we began in 2012. A major impetus for the founding of this non-profit came from my Fulbright SyCip Distinguished Lecturing Award.❮❯- Alumna, Philippines, 2008

var slideIndex4 = 1; showSlides4(slideIndex4); function plusSlides4(n) { showSlides4(slideIndex4 += n); } function currentSlide4(n) { showSlides4(slideIndex4 = n); } function showSlides4(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote4 .mySlides4"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote4 .dot4"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex4 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex4 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex4 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex4 - 1].className += " active"; }FAMILY: PROFESSIONAL PATHWAYS

Scholars whose families accompanied them on their Fulbright expressed that because of the experience their family members pursued international careers and participated in cross-cultural activities in the home communities.

.mySlides5 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot5 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot5:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }We have five children who were greatly impacted by the Fulbright experience. Since our return, our oldest has taught in 4 countries, second oldest taught 3 years in Kuwait, third oldest learned a strategic language and now works for the military and the fourth oldest is bilingual and now works in Australia.- Alumnus, Hungary, 2008

My family and I made community presentations about our host country. We have become more involved in hosting students from my host country. My university hired my wife, who joined me on my Fulbright, to improve my university's social and cultural programming for visiting international students and faculty.- Alumnus, China, 2014

I'd like to mention that my wife, who was a superb "honorary" Fulbright ambassador during 2011-12, has returned to my/our host country on at least three different occasions to help raise funds for underprivileged children, local hospitals, etc. Her activities have been noted on local TV broadcasts in our host country.- Alumnus, Montenegro, 2012

My daughter started a non-profit "Dance Another World" teaching English to elementary school children in an after-school program. This was based on work she did when she joined me for 7 months of my Fulbright grant in Vietnam. She taught the students at Dong Thap U. ballet and their English improved dramatically. I've helped her at events.❮❯- Alumna, Vietnam, 2009

var slideIndex5 = 1; showSlides5(slideIndex5); function plusSlides5(n) { showSlides5(slideIndex5 += n); } function currentSlide5(n) { showSlides5(slideIndex5 = n); } function showSlides5(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote5 .mySlides5"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote5 .dot5"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex5 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex5 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex5 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex5 - 1].className += " active"; }KEY TAKEAWAY

Through participation in the Fulbright U.S. Scholar program, scholars enhanced their careers gaining more recognition for their work and taking on new responsibilities. Some scholars expanded their careers to include new directions and organizations. The program has also impacted career choices of the family members who accompanied scholars during the grant. The next chapter reviews the effect the program had on the scholars’ personal growth.

- PERSONAL GROWTH & INTERCULTURAL SKILLS

-

I returned home forever changed, for the better, due to my Fulbright experiences, bringing with me the experiences I had to share with students, colleagues and others in my field of research.

- Alumnus, Morocco, 2010

53% of scholars indicated that the Fulbright program had an impact on their personal growth. The personal growth that scholars referred to included enhancement of their individual interpersonal skills as well as development of a more global mindset, understanding, and abilities to apply both to their work and personal life.

93% of scholars increased their ability to function in a multi-cultural academic environment. They applied these skills to their teaching and to building collaborations after the program.

.mySlides6 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot6 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot6:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }I gained a good deal of experience in dealing with multicultural student and scientist groups which has improved my ability to deal with similar situations at my home institution. Moreover, the confidence I developed in working in other countries and cultures has allowed me to expand the reach of my institution in countries other than my Fulbright country.- Alumnus, Slovenia, 2011

I am a consultant no longer affiliated with a college/university. I have however used new skills in working with clients. I think I listen more deeply and pay closer attention to details as a result have having had to do the same in Ghana because of the multiplicity of languages spoken, how English is spoken, because names were unfamiliar and because I closely observed cultural norms.❮❯- Alumna, Ghana 2015

var slideIndex6 = 1; showSlides6(slideIndex6); function plusSlides6(n) { showSlides6(slideIndex6 += n); } function currentSlide6(n) { showSlides6(slideIndex6 = n); } function showSlides6(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote6 .mySlides6"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote6 .dot6"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex6 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex6 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex6 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex6 - 1].className += " active"; }95% of scholars improved their intercultural skills and 85% of scholars have seen changes to their interpersonal skills because of the Fulbright grant. They have been applying these skills to better serve international students, minorities, and underserved groups in their professional and personal communities. Some scholars who identified with these groups have been able to use the intercultural skills to navigate their relationships with the majority group.

.mySlides7 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot7 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot7:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }My experience as a Fulbright Scholar gave me a more global perspective in my work as a teacher and administrator. It gave me more empathy for international students and allowed me to better understand the value of diversity.- Alumnus, Lithuania, 2009

[After my Fulbright] I was much more sensitive to cultural differences, not only national differences but all differences. As a result, I was able to help others succeed more than I would have otherwise.- Alumnus, Panama, 2011

I used my understanding of intercultural relationships to better navigate difficult relationships at my home institution where I am a minority.❮❯- Alumna, Belgium, 2008

var slideIndex7 = 1; ShowSlides7(slideIndex7); function plusSlides7(n) { ShowSlides7(slideIndex7 += n); } function currentSlide7(n) { ShowSlides7(slideIndex7 = n); } function ShowSlides7(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote7 .mySlides7"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote7 .dot7"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex7 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex7 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex7 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex7 - 1].className += " active"; }Over 40% of scholars indicated that the Fulbright grant impacted their knowledge and appreciation of world cultures. Scholars developed better understanding of their host communities, which later allowed them to recognize and challenge the stereotypes Americans may have had about their host countries and regions. They saw their acceptance of people from cultural backgrounds different from their own increase and were able to better connect with them.

The Fulbright gave me a heightened cultural awareness about Muslims and life in the Middle East. I thought that I would find a more positive encounter than media images that populate our news channels, but I gained more than just that. As a Fulbright scholar I was given the unique privilege to join the community and have a lot of those negative preconceived notions challenged. I went on the Fulbright with and open mind and eager to learn from my environment and the reward was tremendous.- Alumna, United Arab Emirates, 2014

Scholars, who were born outside of the U.S. had unique experiences coming back to their country of birth on the Fulbright grant, considering their own culture and belonging, and having a changed perspective on their birth/host and home countries.

I was born in my host country, and spent the first 28 years of life there. I spent the last 50 years of my life in the U.S. During this period, I have taken many trips to my (now) host country. I believe there has been a continuum of cultural exchange between the two countries during these trips. The Fulbright program gave me (and my wife) the unique opportunity to further the cause of such cultural exchange over a sustained amount of time (4 months).- Alumnus, India, 2005

85% of scholars reported that their Fulbright grant increased their self-confidence.

The Fulbright enabled me to make a 30-minute film. It was the first time I worked with such a crew of 6 and the experience was invaluable. I am more confident about initiating ambitious projects.- Alumna, Ecuador, 2015

66% of scholars improved their foreign language skills. They used their language knowledge to teach their classes, establish better communication with international students, continue research in the host country, and to build cohesive multi-national communities in the U.S. and across borders.

.mySlides8 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot8 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot8:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }The Fulbright experience in Ecuador impacted my language teaching on my campus (now projected based and entirely in the target language). Since my family traveled with me, the cultural/linguistic impact was dispersed by 5 people, not just one person.- Alumna, Ecuador, 2007

With my strengthened Spanish skills, I have served as a bridge between immigrant and white native-born members of my city and university.- Alumna, Venezuela, 2009

In my 2010 Egypt Fulbright, I taught jazz (in Arabic), researched how musical improvisation is taught in Egypt, and studied the oud. Since returning, I have continued to study Arabic music, including taqasim (improvisation), and given many concerts bringing together Arab and American musicians. I also switched academic fields, leaving classical music to teach the Arabic Language. All of these directly grew out of my life-changing Fulbright in 2010.❮❯- Alumnus, Egypt, 2010

var slideIndex8 = 1; showSlides8(slideIndex8); function plusSlides8(n) { showSlides8(slideIndex8 += n); } function currentSlide8(n) { showSlides8(slideIndex8 = n); } function showSlides8(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote8 .mySlides8"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote8 .dot8"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex8 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex8 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex8 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex8 - 1].className += " active"; }KEY TAKEAWAY

Through participation in the Fulbright U.S. Scholar program, scholars developed skills important for international and cross-cultural collaboration. They applied these skills to their professional and personal lives as discussed further in the report. The next chapter speaks to how scholars applied their work at their home institutions using technical skills gained during the program in addition to intercultural skills.

- HOME INSTITUTION IMPACTS

-

As Chair of the council of faculty in my college, I spend a great deal of time sharing an international research and teaching perspective in part gleaned from my time as a Fulbright scholar.

- Alumnus, France, 2008

During the program, scholars learned new teaching and research methods and expanded their knowledge of their professional area. This chapter explores in detail how scholars applied that knowledge to benefit their home institution.

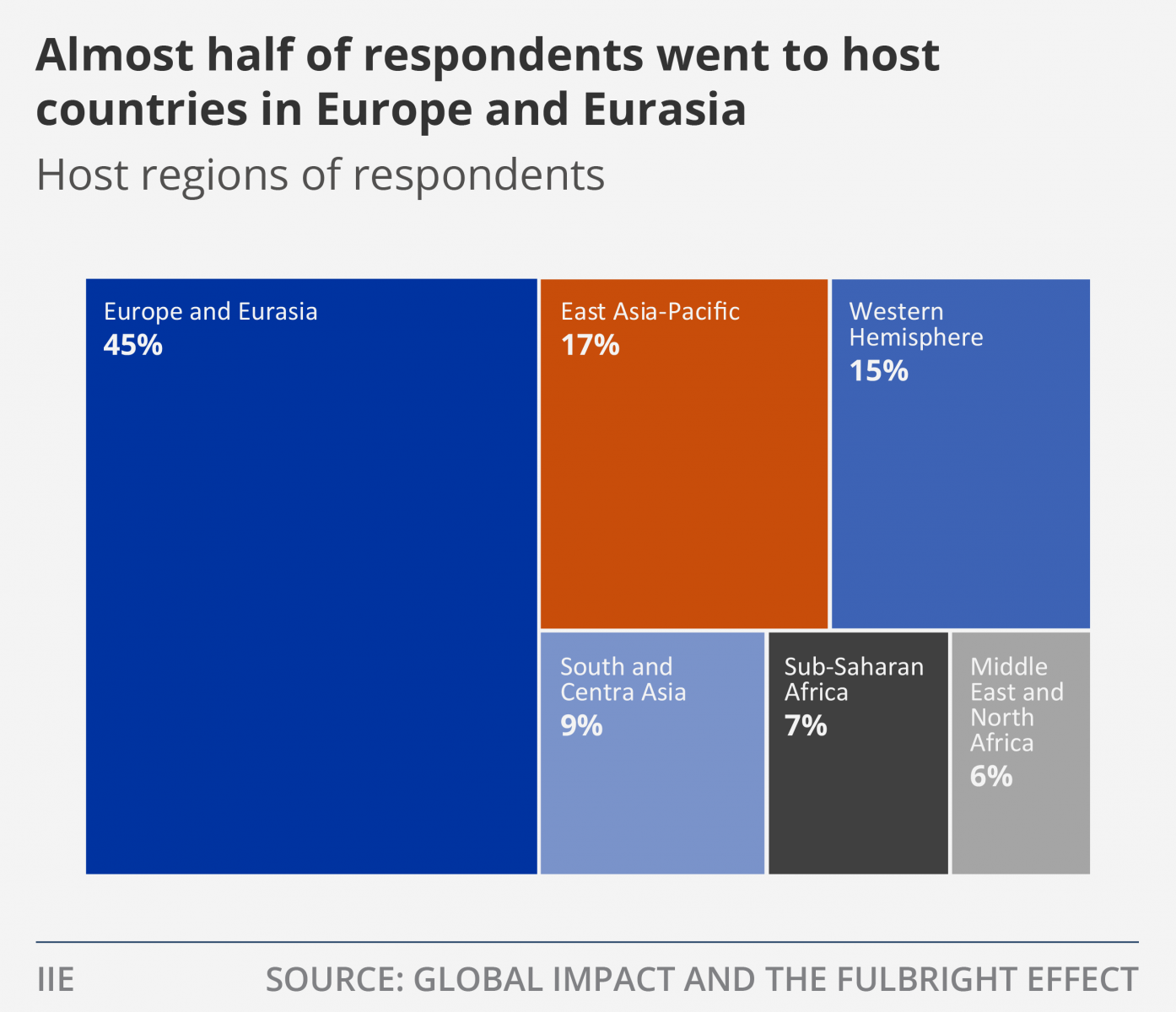

TEACHING

As the majority of Fulbright scholars are academics, teaching, advising, and mentoring students and junior colleagues are significant components of their career. The Fulbright Program contributed to improvements in the scholars’ skills in these areas: 70% improved their lecturing skills and 57% learned new teaching methods. Scholars who had grants with a teaching component experienced higher increases in the lecturing skills and knowledge of teaching methodologies than scholars with just research grants.

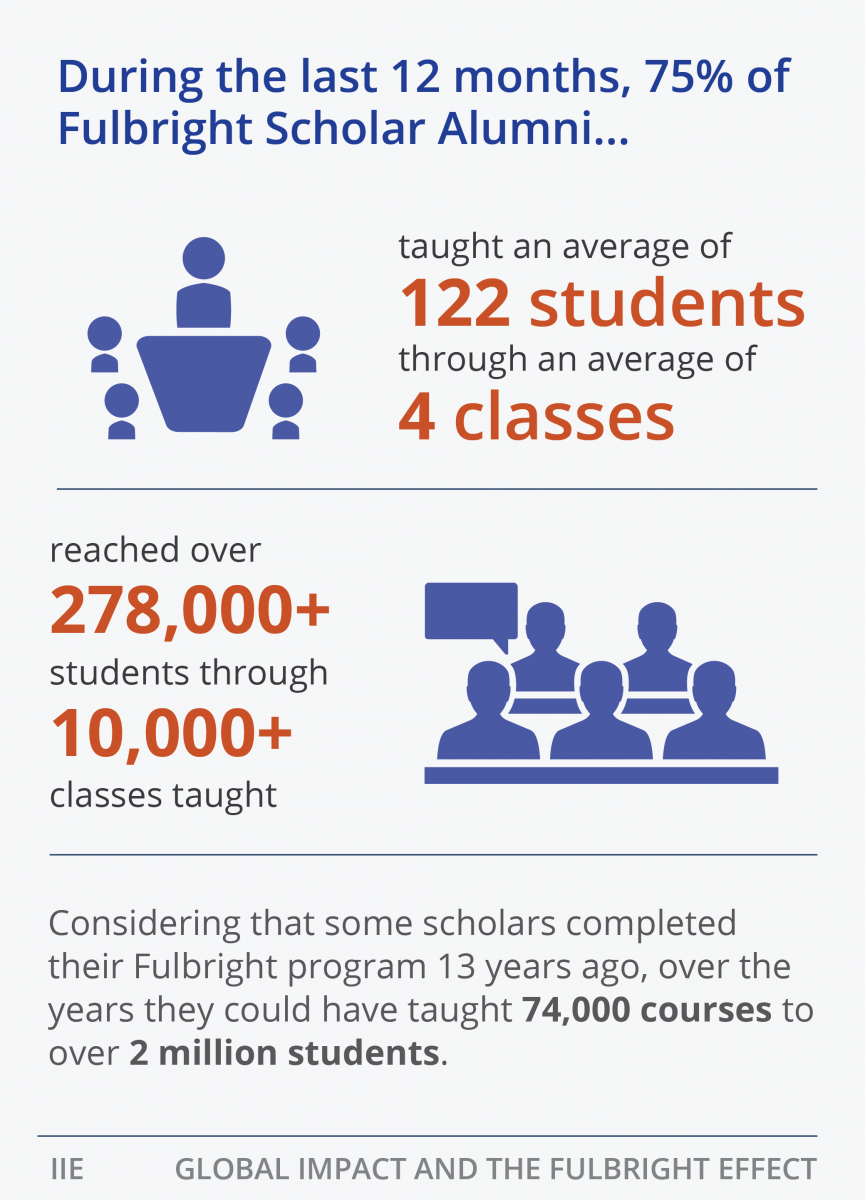

Over 75% of scholars of all grant types taught undergraduate or graduate students in the past 12 months. An average scholar has taught 4 classes to 122 students in the past 12 months. Overall, during that time, scholars reached at least 278 thousand students through over 10 thousand classes. Considering that some scholars completed their Fulbright program 13 years ago, over the years they could have taught 74,000 courses to over 2 million students.

As a result of their Fulbright experience, 1935 scholars (62%) adapted more inclusive teaching practices in their work, and 278 scholars (13%) had new teaching methodologies implemented across their home institution. Because during their grant, scholars found it challenging to teach students with whom they shared different language and cultural references, they had to adjust their content and delivery to be applicable under the circumstance. Upon returning to the U.S., they realized that making these kinds of adjustments to their teaching at home will improve their classes and make them more inclusive for students with diverse backgrounds.

Furthermore, working in and living in another country, scholars increased their understanding and empathy of the diverse students on their campus, including international students, students whose first language is not English, and students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

.mySlides9 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot9 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot9:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }In teaching Chinese students, I gained insights into the experience of a variety of students, not just international ones, who might feel out of place. I needed to adapt teaching methods to a very different type of learner, and that made me think more about how to reach different students.- Alumna, Hong Kong, 2009

Teaching in a different country made me re-evaluate the taken-for-granted ways that I structure courses, grade, and interact with students. Upon returning to my home institution, I revamped my courses, incorporated different pedagogies, and recognized ways to avoid grade inflation.- Alumna, Canada, 2015

After spending months working in the field and lab with students in Brazil who had never had access to a "modern" molecular biology lab, I realized that many of my teaching methods and protocols were unnecessarily complicated and expensive. I am now much better at teaching people from all sorts of research backgrounds.- Alumna, Brazil, 2014

Teaching to students for whom English was a second language was challenging. I developed new materials to make concepts clearer and that did not rely on students' having background cultural knowledge. I found that these new methods greatly increased my ability to convey information to an increasingly diverse student population at my home institution.- Alumnus, Austria, 2009

My work with the charter school is one of the "ripple effects." I brought back a new understanding of how to help children from a different culture to succeed in school. What I learned and brought back has made a difference in students' and teachers' lives. It's not simply a recipe. It's about respecting and having expectations that these children can be successful regardless of their family's standing in the dominant culture. They can learn to love reading if materials are meaningful to them.❮❯- Alumna, South Africa, 2009

var slideIndex9 = 1; showSlides9(slideIndex9); function plusSlides9(n) { showSlides9(slideIndex9 += n); } function currentSlide9(n) { showSlides9(slideIndex9 = n); } function showSlides9(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote9 .mySlides9"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote9 .dot9"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex9 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex9 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex9 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex9 - 1].className += " active"; }ADVISING

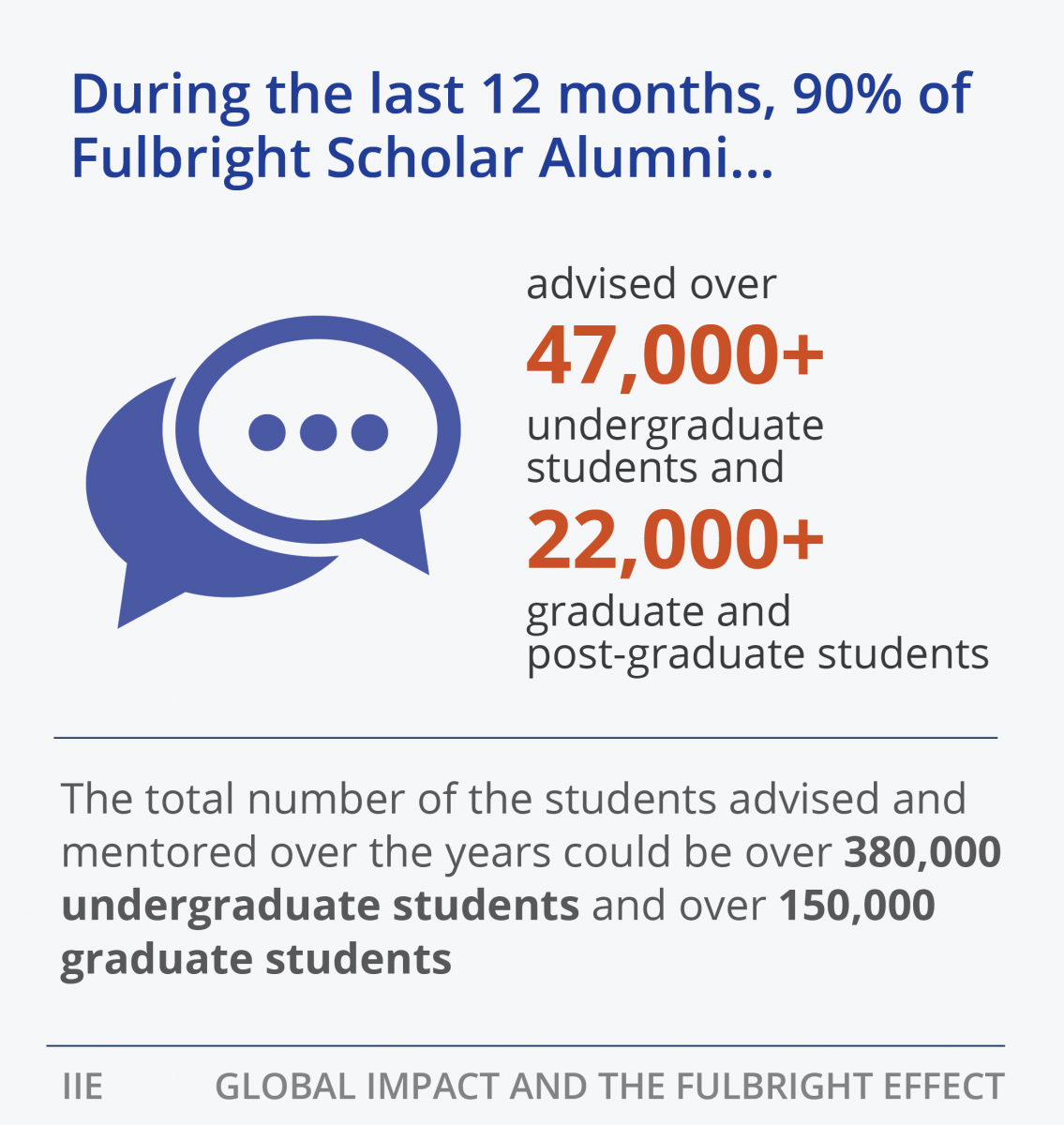

Scholars also applied their grant experiences to changes in their approaches to advising students in their home institutions. Almost 90% of scholars formally and informally advised and mentored students in the past 12 months. During that time, they advised at least 47,256 undergraduate and 22,084 graduate and post-graduate students. Considering the number of years that some scholars had since completing their Fulbright program, the total number of the students advised and mentored over the years could be at least 380,000 for undergraduate and 150,000 for graduate students.

Teaching in Rwanda enabled me to experience what it is like to be a member of a visible minority. This is very different from being a person of color in the US, but nevertheless gave me narrow window into what that experience is like. It's deepened my empathy for minority and international students at my home institution, and I think has made me a more effective advisor for these students.- Alumnus, Rwanda, 2012

FIELD KNOWLEDGE

The Fulbright Program impacted scholars’ understanding of their professional field. Over 90% of scholars gained a deeper understanding of their discipline and research area and valuable field-specific knowledge. 88% of scholars were exposed to new ideas and concepts in their field during their grant. This progress resulted in changes to various areas, including course content in their home institutions and their approach to research.

It was very helpful to understand the nuances of energy and environmental policy compared to conventional knowledge and preconceptions I had prior to my Fulbright experience. My research assumptions about policy effectiveness changed substantially as a result of this experience.- Alumnus, Norway, 2015

RESEARCH METHODS

In addition to gains in technical knowledge, almost 80% of scholars with research grants and 50% of scholars with teaching grants gained new skills to conduct research.

In addition to gains in technical knowledge, almost 80% of scholars with research grants and 50% of scholars with teaching grants gained new skills to conduct research.As a result of their Fulbright experience, 53% of scholars made changes to their research methods. Almost 20% of scholars developed almost 800 new research programs for faculty and students, and 10% had new research methods implemented across their home institution.

.mySlides11 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot11 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot11:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }I was able to take the knowledge learned, in this case, a particular experimental method, and apply this to my research topic back home and able to cite my Fulbright experience to support my cause in my extramural funding applications.- Alumnus, Taiwan, 2014

This experience has enriched my knowledge on research methodology. Since the completion of my Fulbright Program, I have developed a new course on research methodology. I have used many of my [Fulbright] research materials for this course.- Alumna, China, 2011

The data set that I collected during my Fulbright has been used by my home institution for 10 years now to develop statistics labs with a cross-cultural component. This aids my US students with both statistics and exposure to data from different cultures.❮❯- Alumna, Norway, 2008

var slideIndex11 = 1; showSlides11(slideIndex11); function plusSlides11(n) { showSlides11(slideIndex11 += n); } function currentSlide11(n) { showSlides11(slideIndex11 = n); } function showSlides11(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote11 .mySlides11"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote11 .dot11"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex11 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex11 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex11 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex11 - 1].className += " active"; }CURRICULA

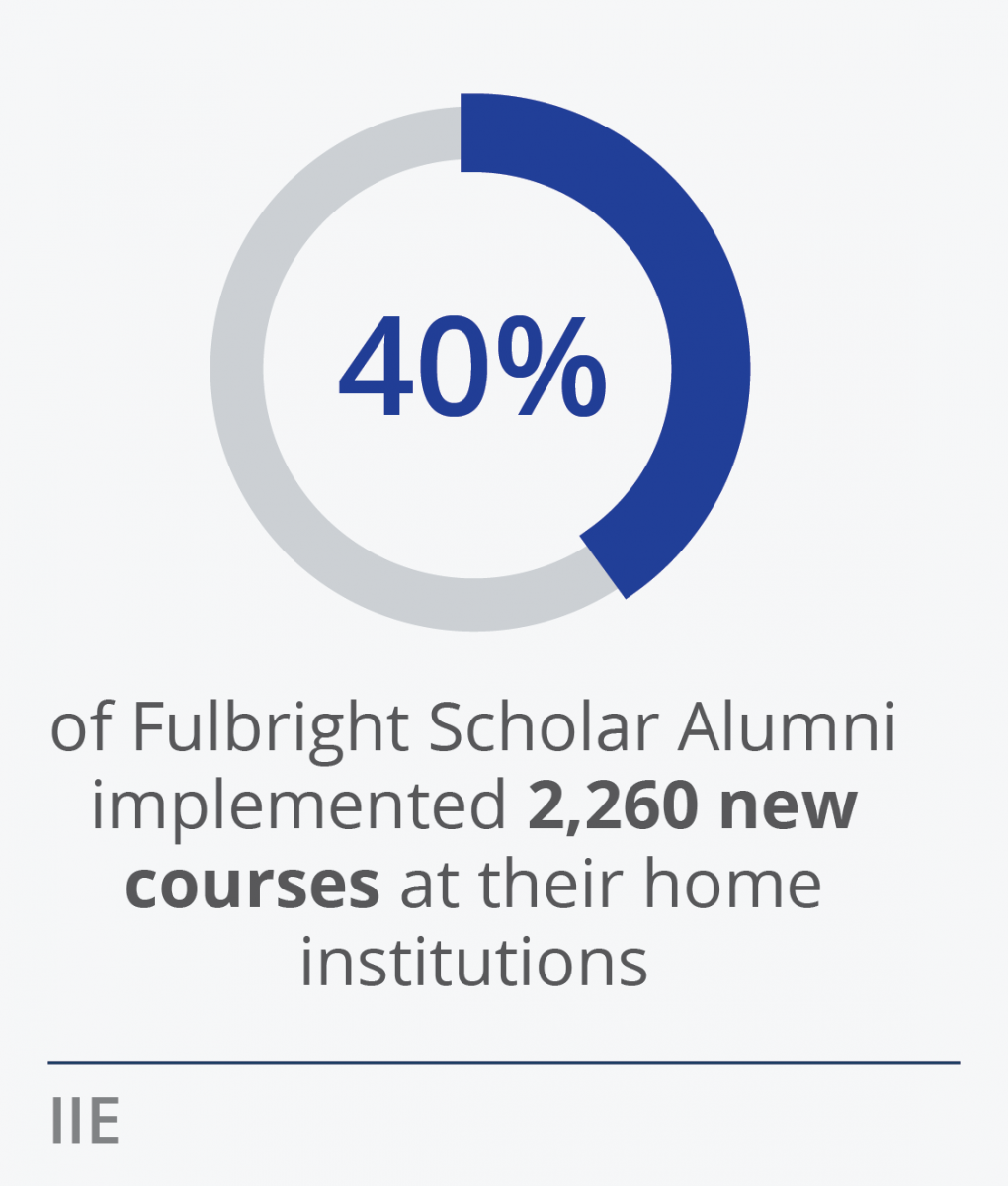

As a result of their Fulbright experience, 78% of scholars adapted content of existing courses or curricula and 66% developed new courses or curricula based on developments in their understanding of their discipline.

As a result of their Fulbright experience, 78% of scholars adapted content of existing courses or curricula and 66% developed new courses or curricula based on developments in their understanding of their discipline.

.mySlides12 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot12 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot12:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }I reworked my core course on U.S. history to reflect what I learned teaching in Brazil. The class was completely reworked because I felt that the presentation to people outside the U.S. was a more satisfying way of presenting the arguments I wanted to make.- Alumnus, Brazil, 2010

I taught a class on the American civil rights movements in Turkey that I had taught in the US. I was in Turkey after Gezi Park and Tacsim Square, so the work was sadly relevant. I learned how the two countries were different and the same and allowed my students to educate me on how they saw what was different and what was the same. This conversation I was able to take back to my classes in the US.❮❯- Alumna, Turkey, 2014

var slideIndex12 = 1; showSlides12(slideIndex12); function plusSlides12(n) { showSlides12(slideIndex12 += n); } function currentSlide12(n) { showSlides12(slideIndex12 = n); } function showSlides12(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote12 .mySlides12"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote12 .dot12"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex12 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex12 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex12 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex12 - 1].className += " active"; }Some scholars leveraged their grant experience to support undergraduate and graduate programs.

My Fulbright experience has been helpful in demonstrating my department's worthiness to be granted a new MA program. This, in turn, will help teachers and other people in my region in their professional development. My region is traditionally recognized as provincial and culturally impoverished. My grant has contributed to the changing perception of my region.- Alumnus, Spain, 2014

INNOVATIONS AND GRANTSScholars applied the knowledge they learned during their Fulbright experience to introduce innovative practices and propose innovative approaches which in many cases were recognized and awarded additional grant funding.

.mySlides13 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot13 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot13:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }Through Fulbright, I learned about a best practice to connect students with working professionals, to increase student understanding of the world of work. After returning to the US, I successfully applied for a grant from the state of CA to develop a pilot of this model - the first such pilot in the US.- Alumna, United Kingdom, 2015

This collaborative teaching and research method that I practiced in Romania resulted in NSF funding which supported the development and research of a new teaching method. Two NSF grants supported a nanotechnology and a robotics class to be taught with this teaching by design method in the following two years.- Alumnus, Romania, 2009

After returning from my Fulbright fellowship, I applied for (and was awarded) a National Institute of Health (National Institute on Aging) 4-year R01 grant that was over $2 million. The pilot data and experiences I collected while a Fulbright scholar directly impacted my ability to be competitive for this grant.❮❯- Alumna, Finland, 2010

var slideIndex13 = 1; showSlides13(slideIndex13); function plusSlides13(n) { showSlides13(slideIndex13 += n); } function currentSlide13(n) { showSlides13(slideIndex13 = n); } function showSlides13(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote13 .mySlides13"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote13 .dot13"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex13 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex13 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex13 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex13 - 1].className += " active"; }KEY TAKEAWAY

Scholars used their enhanced technical and intercultural skills to their teaching, research, and creative work at their home institution. Through these changes they better supported their students and introduced new developments into their professional field. The next chapter discusses how scholars applied their increased understanding of the value of international exchange to internationalize their campuses.

- PROMOTING INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE

-

My experience as a visitor in a foreign country made me much more interested in providing a positive experience for international visitors to my own academic institution. Ever since, I have been extremely active in hosting our foreign visitors, providing them with a positive social experience, and helping them in any way I can with their academic projects.

- Alumnus, Canada, 2012

68% of scholars became more involved with international education on their campus upon return from the Fulbright Program. They engaged with international students and faculty, advocated for international exchange programs, in particular for Fulbright programs, and developed opportunities for study abroad and hosting of international academics.

As a result of the efforts described in this chapter, 50% of scholars witnessed increased institutional support for international programming and 36% of scholars observed their institutions dedicate more resources to implementing international programs.

Furthermore, these efforts led to increased campus internationalization through further student and scholar travel abroad, supported by the home institution, and through international students and academics.

Support for study and teaching abroad has increased. We now have a number of international programs which take students and faculty to all areas of the world. These programs vary from summer programs, to full semester and full year study programs, and they take place in all parts of the world. There are also a number of ways that students who wish to participate in these programs can get financial support.- Alumna, Mexico, 2005

See chapters on Home Institution Impacts and Cross-Cultural Understanding for other avenues of campus internationalization such as incorporating international perspectives in the daily teaching.

PROMOTING STUDY ABROAD

85% of scholars encouraged their students to study abroad. Some communicated the value of studying abroad and others inspired their students by sharing their Fulbright experience.

My home institution students are often from small rural white communities. I infuse anecdotal information gleaned from my Fulbright. They have commented on evaluations about how this helped their learning. One student said she planned to teach abroad due to this.- Alumna, Georgia, 2013

CREATING A SUPPORTIVE ENVIRONMENT FOR STUDY ABROAD

Scholars felt motivated to create international exchange opportunities for their students and faculty. They joined existing or started new initiatives related to international exchange and, as a result, generated interest and developed more opportunitiesfor international students to study at their home institutions. .mySlides14 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot14 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot14:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }One example of using knowledge and understanding gained during my Fulbright grant to improve my home community was the effort I made to bring international awareness to my home campus. Since then we have started an International Programs office and are in the process of setting up study abroad courses.- Alumnus, Germany, 2009

I am now the Graduate Admissions Committee Chair in my department. My Fulbright experience has allowed me to expand significantly my vision of recruiting, mentoring and guiding foreign graduate applicants from that region.- Alumnus, Costa Rica, 2014

Worked collaboratively with local and national experts to revise academic advising and enrollment efforts to increase student engagement in general, and student participation in study abroad activities - specifically first-generation college students, students of color and Pell-grant eligible students who attend two-year colleges.❮❯- Alumnus, Germany, 2012

var slideIndex14 = 1; showSlides14(slideIndex14); function plusSlides14(n) { showSlides14(slideIndex14 += n); } function currentSlide14(n) { showSlides14(slideIndex14 = n); } function showSlides14(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote14 .mySlides14"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote14 .dot14"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex14 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex14 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex14 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex14 - 1].className += " active"; }Scholars who participated in the IEA Seminars felt well-equipped to guide their home institutions in international exchange. They have been able to better advise students and create institutional advising support for students interested in study abroad programs.

.mySlides15 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot15 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot15:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }As an exchange program administrator, I was able to use my Fulbright experience to advise students on potential study abroad opportunities and I felt like I had a much better grasp of how the German (and European) higher education system works.- Alumna, Germany, 2008

After returning from an IEA seminar, I've resurrected a reciprocal exchange for our institution (in the host country) and also organized & led two trips to the host country for undergraduate students, including taking faculty who had not been there previously. I was and am the lead on these initiatives, and students receive academic credit at my home institution for participating in each.❮❯- Alumna, United Kingdom, 2013

var slideIndex15 = 1; showSlides15(slideIndex15); function plusSlides15(n) { showSlides15(slideIndex15 += n); } function currentSlide15(n) { showSlides15(slideIndex15 = n); } function showSlides15(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote15 .mySlides15"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote15 .dot15"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex15 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex15 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex15 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex15 - 1].className += " active"; }DEVELOPING INTERNATIONAL EXCHANGE PROGRAMS

The Fulbright experience gave me the courage and the skills to carry out these programs.- Alumna, Egypt, 2006

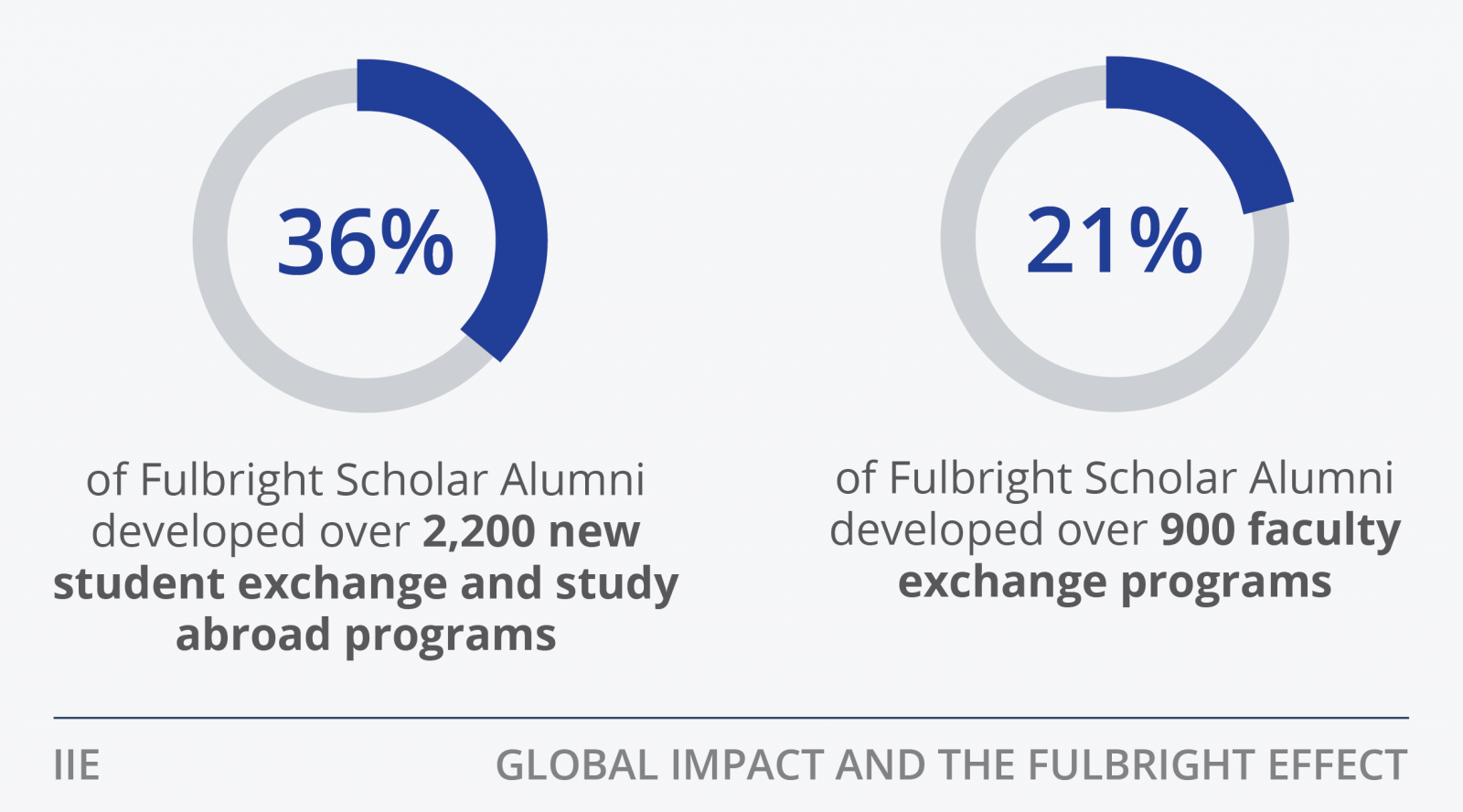

36% of scholars developed over 2200 new student exchange programs and study abroad programs and 21% developed over 900 new faculty exchange programs. Scholars who completed their Fulbright programs earlier had more years to develop such programs.

Home Institution: Study Abroad Programs

At their home institutions, scholars organized and led the student study abroad programs themselves. Additionally, some scholars have been able to make the study abroad programs a formal university requirement.

.mySlides16 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot16 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot16:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }Currently I am engaged in organizing a student exchange program with my university and several Italian universities. This exchange program was motivated by my experience working in Italy universities on two separate Fulbright grants.- Alumna, Italy, 2015

I became a "trip leader" taking students from my home institution to Ukraine for a three-week visit (which fulfills a university requirement) and introduced basic language skills prior to the trips. I did this for eight sequential years following my return to my home institution❮❯- Alumnus, Ukraine, 2005

var slideIndex16 = 1; showSlides16(slideIndex16); function plusSlides16(n) { showSlides16(slideIndex16 += n); } function currentSlide16(n) { showSlides16(slideIndex16 = n); } function showSlides16(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote16 .mySlides16"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote16 .dot16"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex16 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex16 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex16 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex16 - 1].className += " active"; }Home Institution: Bringing International Students and Faculty to Campus

Hosting international students and faculty is another way to internationalize the scholar’s home campus. 51% of scholars reported that, as a result of their own participation in the Fulbright Program and their advocacy for international exchange, their home institution hosted over 4800 Fulbright Scholars and scholars invited through other avenues.

.mySlides17 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot17 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot17:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }Along with another colleague at my home university, we applied for a SIR Fulbright, and are bringing a Russian scholar to our campus for the 2018-2019 academic year.- Alumnus, Russia, 2013

Invited the pre-eminent filmmaker of the country for a week-long residency (and raised considerable money to do this). He attended film screenings and gave lectures, was the first African director ever to visit the state at length.- Alumna, Senegal, 1993; Austria, 2006

As a result of my participation on the Fulbright seminar, I have received inquiries from other visiting international delegations to visit my home institution and meet with students, faculty, and administrators.❮❯- Alumna, Russia, 2013

var slideIndex17 = 1; showSlides17(slideIndex17); function plusSlides17(n) { showSlides17(slideIndex17 += n); } function currentSlide17(n) { showSlides17(slideIndex17 = n); } function showSlides17(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote17 .mySlides17"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote17 .dot17"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex17 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex17 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex17 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex17 - 1].className += " active"; }Jointly with Host Institution

One type of collaboration that scholars established with their host institutions was establishment of student study abroad programs between the institutions.

.mySlides18 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot18 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot18:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }

We wrote a memorandum of understanding that we presented to the student-exchange office at the University of Botswana, and I did the same at Utah State University upon return home. As a result of our efforts the two institutions established a student exchange program.- Alumnus, Botswana, 2008

I created liaisons between educators at my host institution in Denmark and educators in a number of different institutions in my home state of North Carolina that yielded educational exchanges between Denmark and US students and faculty.- Alumna, Denmark, 2008

After completing my Fulbright, I initiated a faculty exchange program with my host institution. To make this exchange work, I partnered with universities across the state as well as other organizations to ensure a rich experience for the visiting scholars as well as communities across the state.❮❯- Alumna, Albania, 2013

var slideIndex18 = 1; showSlides18(slideIndex18); function plusSlides18(n) { showSlides18(slideIndex18 += n); } function currentSlide18(n) { showSlides18(slideIndex18 = n); } function showSlides18(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote18 .mySlides18"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote18 .dot18"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex18 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex18 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex18 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex18 - 1].className += " active"; }FULBRIGHT CHAMPIONS

Individual Efforts

85% of scholars encouraged their peers to apply for a Fulbright grant, and 73% encouraged their students to do the same. They gave presentations about their experience, served on panels about study abroad and Fulbright, and supported individual students and colleagues through the application process.

.mySlides19 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot19 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot19:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }I have been very active in mentoring students in applying for research Fulbrights since I've received my last grant. This year alone, three of my former undergraduate students received Fulbright grants.- Alumna, Burkina Faso, 2007

I gave a presentation about my Fulbright experience when I returned. I mentored others in applying for Fulbright grants at my home institution. I also presented a workshop on how to apply for a Fulbright grant for the university at large. In addition, I served on the university committee that interviewed our university students who wanted to apply for student Fulbright’s.❮❯- Alumnus, Hungary, 2009

var slideIndex19 = 1; showSlides19(slideIndex19); function plusSlides19(n) { showSlides19(slideIndex19 += n); } function currentSlide19(n) { showSlides19(slideIndex19 = n); } function showSlides19(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote19 .mySlides19"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote19 .dot19"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex19 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex19 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex19 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex19 - 1].className += " active"; }76% of scholars saw their colleagues become more interested in applying for the Fulbright program because of their experience.

My colleagues' interest level skyrocketed because they witnessed that it can be done to move overseas with two small children, increase your professional status, and maintain your sanity. It's challenging but the rewards are limitless.- Alumna, Japan, 2015

Scholars also shared the value of the program with the greater community through writing books and blogging about their Fulbright experiences.

.mySlides20 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot20 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot20:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }I was already retired when I received my Fulbright: I wrote a memoir of my two Fulbrights and reflections on the edges of my career they marked—I had an earlier award to Italy, 1974-75. The memoir considered what I learned about national cultures, teaching, literature and of course myself from these two experiences, which I still enjoy and value.- Alumnus, Portugal, 2011

I hosted a blog about my Fulbright that has 110 followers (who get blog updates via email) with 38,540 visits to the site and 125,000 views. I established a website of photographs featured in a Fulbright art exhibition and another on robotics with my host institution.❮❯- Alumna, Ireland, 2013

var slideIndex20 = 1; showSlides20(slideIndex20); function plusSlides20(n) { showSlides20(slideIndex20 += n); } function currentSlide20(n) { showSlides20(slideIndex20 = n); } function showSlides20(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote20 .mySlides20"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote20 .dot20"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex20 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex20 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex20 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex20 - 1].className += " active"; }Formal Fulbright Outreach Efforts

57% of scholars participated in formal Fulbright outreach activities since program completion. For example, 21% of scholars participated as an alumnus/alumna speaker in Fulbright conferences, seminars, webinars or other activities. Some have also been involved with the Fulbright Association and local Fulbright Chapters.

When I came back I became very active in the Fulbright Chapter, later becoming the president of the chapter for two consecutive years. I invited new Fulbright scholars of color to be part of the board in order to mirror the diversity of the city. I created connections with colleges and universities and consulates. I used the brand of Fulbright to brand our chapter! I am currently very active at all levels in my community.- Alumna, Venezuela, 2005

56% of respondents maintained contact with Fulbright Commissions and U.S. embassies in their host countries. A third has served as panel reviewers, and 21% participated in events and lectures organized by the Fulbright Commissions and embassies. Scholars were interested in being more involved with the outreach and review processes and to serve as resources for the Fulbright Program.

Since landing a tenure track job, I have enriched my home community by serving as scholarship adviser--a post we did not have and one that I created in order to promote the Fulbright Commission's offerings and to support students in their applications. I have also served on the Fulbright Commission's selections committee at my home institution.- Alumna, Germany, 2007

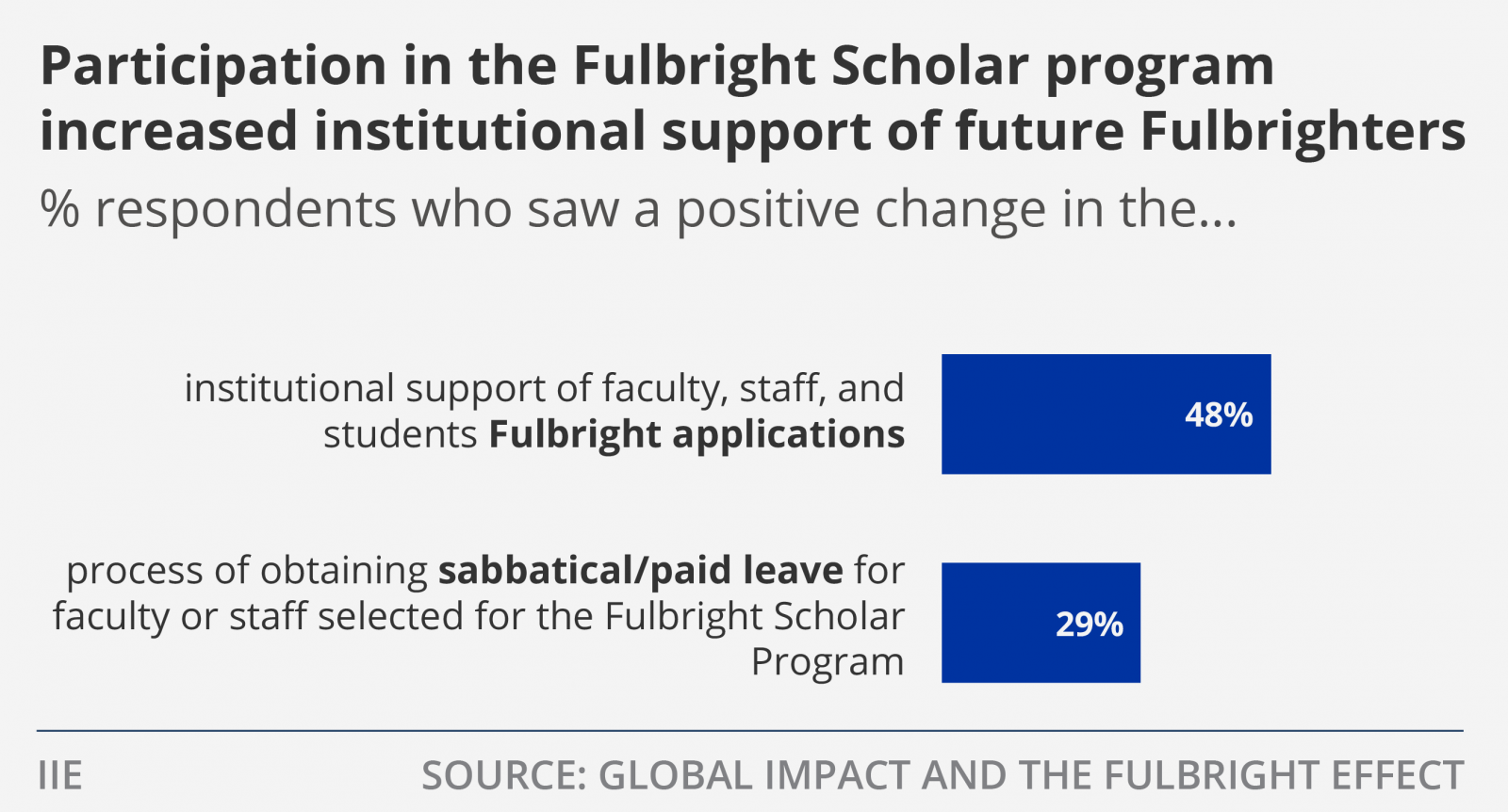

Institutional Support for Fulbright

42% of scholars advocated more Fulbright-friendly policies at their home institution. As a direct result of the scholars’ participation in the Fulbright Program and their advocacy, 31% of institutions designated over 850 Fulbright Scholar Liaisons and Fulbright Program Advisors. Over the years, 25% of scholars personally participated in formal Fulbright advising for prospective candidates as a Fulbright Program Advisrs or Fulbright Scholar Liaisons.

For many years I was the campus Fulbright Liaison for faculty members and students. Three faculty members who I encouraged to apply for Fulbright were awarded them last year. Although I am no longer liaison, I work closely with the new one.- Alumna, Ecuador, 2005

Scholars in other administrative roles on campus have also been able to directly promote the U.S. and Visiting Fulbright program.

After completing my Fulbright grant I ran for and was elected to the advisory committee of the Center for Latino and Latin American Studies at my university and served for a number of years. I supported expansion of the number of Fulbright visitors to our campus and encouraged my colleagues to apply for the program.- Alumna, Peru, 2005

Institutions also increased their support for application process and for participation in the Fulbright program.

.mySlides21 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot21 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot21:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }Upon my first Fulbright in 1998, my institution required I apply for a sabbatical in order to have the time off teaching at my institution. Through [my] lobbying, Fulbright Awards are now viewed as prestigious and given necessary time.- Alumnus, Philippines, 2005

My institution made substantive changes in the way it dealt with Fulbright recipients. The university developed a plan to provide health insurance for faculty during their Fulbright grants and agreed to continue contributions to retirement accounts even though faculty were not "formally employed" by the university during their tenures as Fulbright participants. Such recognition of the importance of the Fulbright programs by the university was seen by faculty as a positive development.❮❯- Alumnus, Egypt, 2010

var slideIndex21 = 1; showSlides21(slideIndex21); function plusSlides21(n) { showSlides21(slideIndex21 += n); } function currentSlide21(n) { showSlides21(slideIndex21 = n); } function showSlides21(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote21 .mySlides21"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote21 .dot21"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex21 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex21 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex21 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex21 - 1].className += " active"; }Scholars recognize that often times it is the effect of having multiple Fulbright scholars and students on campus that creates the change in institutional policies towards the Fulbright program and other international exchanges.

.mySlides22 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot22 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot22:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }I was one of numerous Fulbright recipients who collectively encouraged institutional change.- Alumnus, Argentina, 2006

My home institution is very supportive of Fulbright scholars and students, both those visiting, as well as those of us visiting other countries. Thus, although such programs have strengthened at my home institution since my Fulbright, this is not necessarily a direct result of my award, but my colleagues' and student awards as well.❮❯- Alumnus, United Kingdom, 2014

var slideIndex22 = 1; showSlides22(slideIndex22); function plusSlides22(n) { showSlides22(slideIndex22 += n); } function currentSlide22(n) { showSlides22(slideIndex22 = n); } function showSlides22(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote22 .mySlides22"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote22 .dot22"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex22 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex22 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex22 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex22 - 1].className += " active"; }Of the 59% of scholars who reported no change to the institutional policy in support of the Fulbright program, some did not report change because their institutions were already highly internationalized, while others encountered challenges and disinterest from their institutions.

KEY TAKEAWAY

First-hand experience of the benefits of the international academic exchange led scholars to promote campus internationalization at their home institutions. Scholars also actively served as informal Fulbright champions encouraging their students and colleagues to pursue the Fulbright grants and working with their departments to increase institutional support for Fulbrighters. Scholars also combined their technical skills and positive belief in the value of international experience to maintain and develop international collaborations that are discussed in more detail in the next chapter.

- INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIONS

-

My interest in international collaborations was increased by my Fulbright experience. This led to my participation in a Fulbright Specialist project in Iceland. This has led to continuing interactions with colleagues there in both teaching and research areas.

- Alumnus, Thailand, 2011

Continuation and increase in international collaborations indicates that U.S. Fulbright scholars continue to prioritize these types of collaborations and opportunities for international exchange well after their Fulbright experience.SKILLS FOR INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATION

90% of scholars widened their research networks during their Fulbright Program. They continued leveraging these networks for collaborations after completing the program. Scholars developed research collaborations with their host institutions and other institutions and colleagues in their host country and other countries.

.mySlides23 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot23 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot23:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }The greatest gain was in the research networks and collaborations that resulted from the research abroad. This has continued to be a productive part of my work life, and I have invited and enabled colleagues on exchange here in the US.- Alumna, Norway, 2007

The contacts I made while in Ireland enabled me to meet (by internet and, in many cases, eventually in person) many excellent mathematicians working on related problems, about whom I had been unaware. These contacts remain useful ten years later.❮❯- Alumnus, Ireland, 2009

var slideIndex23 = 1; showSlides23(slideIndex23); function plusSlides23(n) { showSlides23(slideIndex23 += n); } function currentSlide23(n) { showSlides23(slideIndex23 = n); } function showSlides23(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote23 .mySlides23"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote23 .dot23"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex23 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex23 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex23 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex23 - 1].className += " active"; }From their collaboration during the Fulbright Program, scholars learned best practices in international collaboration, such as the importance of ownership on behalf of all parties.

My experiences in Malawi brought my cultural awareness to a new level. I had thought my primary purpose was to facilitate the host program's success. Only after returning home and learning that nearly all of my curricular efforts (leading the team as we designed a revised curriculum with all new course syllabi including outcomes driven learning objectives) were abandoned, did I begin to know how critical it was for the host to lead and own any revisions to their program.- Alumna, Malawi, 2012

COLLABORATION TYPES

96% of scholars increased their knowledge and understanding of the capacity of higher education institutions in the host country. Coupled with the networks these scholars established during their visit, scholars have continued these relationships with their host country through professional collaborations, exchange, and research trips. Furthermore, 67% of scholars returned to their host countries for professional activities.

Collaborations with Host Institution

Many scholars built on their relationship with the host institution colleagues to continue working together on projects they started during the Fulbright program and to develop new projects. Additionally, since completing their Fulbright Program, 39% of scholars developed new curricula for their host institution.

.mySlides24 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot24 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot24:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }Due to this opportunity I established a new - and main - research collaboration with a [host country] colleague. We have started a project now that has lasted 5 years and involved a relatively large number of undergraduate and graduate students at my home institution, together with my home institution colleagues. In this context we have substantially pushed forward research on automated mathematical discovery.- Alumnus, Belgium, 2013

I developed a research program with my Mexican collaborators that was funded by the National Science Foundation. The collaboration led to an endangered tree species conservation network in Mexico and Central America that has taken on a life of its own. The scientific and conservation work is still ongoing, as is the distributed graduate seminar we co-taught.- Alumna, Mexico, 2011

Returned a year later with two U.S. colleagues to conduct a one-week short course in their subfield (manufacturing engineering) at host, funded by home institution. The proposal for this was developed jointly, including permanent curriculum expansion.- Alumnus, Sri Lanka, 2005

I co-designed one new course and substantially revised another one with a colleague from my host University. He continues to teach those courses.❮❯- Alumnus, Democratic Republic of the Congo, 2009

var slideIndex24 = 1; showSlides24(slideIndex24); function plusSlides24(n) { showSlides24(slideIndex24 += n); } function currentSlide24(n) { showSlides24(slideIndex24 = n); } function showSlides24(n) { var i; var slides = document.querySelectorAll("#quote24 .mySlides24"); var dots = document.querySelectorAll("#quote24 .dot24"); if (n > slides.length) { slideIndex24 = 1 } if (n < 1) { slideIndex24 = slides.length } for (i = 0; i < slides.length; i++) { slides[i].style.display = "none"; } for (i = 0; i < dots.length; i++) { dots[i].className = dots[i].className.replace(" active", ""); } slides[slideIndex24 - 1].style.display = "block"; dots[slideIndex24 - 1].className += " active"; }Home and Host Student Collaborations

After their Fulbright, scholars have also been able to promote opportunities for their home and host students to collaborate.

.mySlides25 { display: none; padding: 20px 40px 20px 40px; text-align: center; } .dot25 { cursor: pointer; height: 12px; width: 12px; margin: 0 6px; background-color: #ddd; border-radius: 50%; display: inline-block; transition: background-color 0.6s ease; } /* Add a background color to the active dot/circle */ .active, .dot25:hover { background-color: #1b3a60; }I was a Fulbright Scholar in Kenya. It was glorious. Thank you. I invited 6 students and one faculty member from my host institution to travel to the U.S. to work with my students for a 10-day cultural/educational exchange. We made original films together in our 48 Hour Film Festival. We merged cultures and my American students gained so much insight about the world, art, identity, and cultural acceptance.- Alumnus, Kenya, 2014