A Daunting Responsibility, But an Exhilarating Opportunity: A Conversation with Dr. Elizabeth Rink and Dr. Gregory Poelzer, Fulbright Arctic Initiative Cohort III Co-Lead Scholars

The Fulbright Arctic Initiative III will bring together a network of professionals, practitioners, and researchers from the United States, Canada, the Kingdom of Denmark (including Greenland and the Faroe Islands), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden for three seminar meetings and a Fulbright exchange experience to address key research and policy questions related to creating a secure and sustainable Arctic.

The third cohort of the Fulbright Arctic Initiative, which is currently accepting applications through September 15, 2020, will stimulate international research collaboration on Arctic issues while increasing mutual understanding between people of the United States and member countries of the Arctic Council. Using a collaborative, multidisciplinary approach, Fulbright Arctic Initiative III will utilize the expertise of academic researchers in the natural and social sciences, Indigenous and local knowledge holders, professionals in the fine arts and liberal arts, as well as practitioners working in various fields.

We recently learned more about the upcoming Fulbright Arctic Initiative III by talking to Co-Lead Scholars Dr. Elizabeth Rink, Associate Professor in Health and Human Development at Montana State University; and Dr. Gregory Poelzer, Professor in the School of Environment and Sustainability at the University of Saskatchewan. In this conversation, Beth and Greg discussed their previous Arctic experience, their return to the Arctic Initiative, and the transformative impact of Arctic research and building mutual understanding.

1. Why did you decide to participate to the Fulbright Arctic Initiative?

Beth: Why the Arctic Initiative? I work primarily in community-based participatory research with indigenous peoples; research that addresses the social, cultural, familial and structural determinants of sexual and reproductive health. I participated in Cohort II in the “Resilient Communities” research group. So, for me, having worked with indigenous communities in Greenland, and elsewhere in North America, having the opportunity to continue that research at the University of Oulu with Sami people in the Utsjoki Region of Northern Finland was very attractive to me on a professional level. Being there, building connections with local people and learning about their approaches and attitudes to sexual and reproductive health, and their related social, cultural, psychological, structural influences, is something you can’t manufacture in a classroom.

More personally, the Arctic Initiative places great emphasis on interdisciplinary groupwork—which is pretty unique in scholarship. Interdisciplinary work can stretch you intellectually and emotionally: most of us are used to working independently on a specific topic, without really having to consider other disciplines or outside perspectives. The experience was amazing and insightful to work with people from totally different backgrounds! To get to know and trust others on my research team, getting to know local community members over weeks and months, is unique. While my individual fieldwork was great, the groupwork meetings were the best.

Greg: I totally agree with Beth! It’s personally and professionally enriching.

I came into the Arctic Initiative in Cohort I as the lead for the Energy research group. My areas of study focus on comparative public policy on Northern development and Indigenous relations, primarily in Arctic and sub-Arctic areas. I’ve participated in well over 100 research and working trips and field seasons across the Arctic. But, the Fulbright Arctic Initiative experience of working in research groups, and collaborating between those groups towards broad policy goals, was definitely different. You’re not picking your research partners, so you really have to make it work. What helps is that the collection of scholars that we’ve worked with are kindred spirits, with the same passion for community and academic work that we have.

2. Both of you participated in previous Arctic Initiative cohorts. What will your role be for this cohort?

Beth: In previous cohorts, Greg and I were independent scholars—we did field work on our individual research projects, meeting with other members of our research teams and members of the cohort to discuss our findings, provide feedback, and work on shared policy recommendations for the Arctic region.

This time, Greg and I serve as “Co-Lead Scholars.” We’re bringing our experiences from different cohorts, and we will be providing scientific leadership to the 16 members of the cohort during their research in the field. We’ll have three in-person meetings—in Canada, Norway, and the United States—with the researchers meeting every month virtually to collaborate and update one another on their progress. As Co-Lead Scholars, we will provide education and training through a series of webinars. For example, we’re going to conduct a webinar on “How to Work with Policy Makers,” as researchers typically don’t have a lot of experience working with government officials on policy recommendations. Members of the cohort can also meet independently in their groups, if they wish.

Greg: I was happy to receive Beth’s call, asking me to participate as a Co-Lead Scholar—she’s a great research partner. While we won’t be out in the field, we know how crucial it is to have support when working on huge, global topics, and working with people from very different backgrounds. There are scientists, researchers, and others who work in areas that “make sense” for the Arctic (public policy, environmental science, indigenous studies, security studies, etc.), but we also collaborate with artists, community organization professionals, and other people from diverse professional backgrounds. We benefited greatly from the tremendous leadership from Ross Virginia and Mike Sfraga during our tenure as Fulbright Arctic Initiative Scholars. It is our turn to give back and help facilitate the research opportunities of the next generation of Northern scholars.

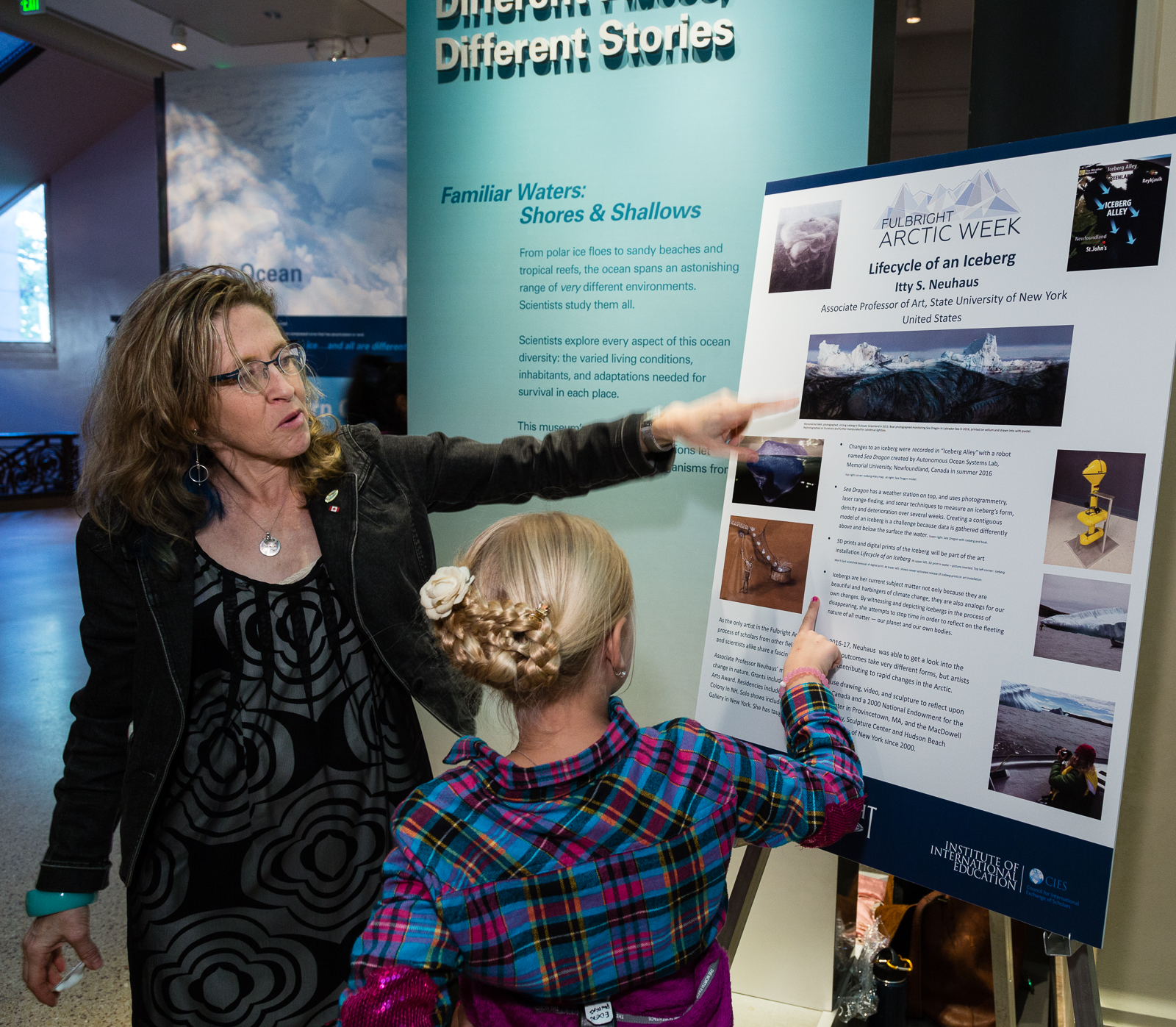

Fulbright Arctic Scholars and U.S. Arctic Youth Ambassadors meet with museum curators at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History.

3. How does working with international scholars benefit the Initiative’s research and policy recommendations?

Greg: I would say that the Fulbright Arctic Initiative’s model of international collaboration is invaluable. The issues that countries in the Arctic face are multinational, and they require solutions from many perspectives. Working with scholars, professionals, and others from different disciplines and backgrounds, in a foreign environment, gets you outside of your local community and ways of thinking. Having different cultural or national lenses on issues in security, the environment, and policy allow you to learn how other communities define the problem, how they work—it actually makes coming up with policy recommendations or solutions easier. It’s a daunting responsibility, but an exhilarating opportunity.

Beth: Exactly. A real-life example that I think speaks to this issue is reindeer herding and husbandry. Indigenous peoples across the Arctic have lived and worked with livestock, most notably reindeer, for thousands of years. Groups, such as the Sami people, have moved across Russia, Finland, Sweden, Norway, and other locations prior to our contemporary state borders, and thus have a very different idea of the landscape, the environment, and the animals that live there. It’s hard to imagine having a nuanced idea of that area without the input of peoples who have lived there, in various capacities, for thousands of years, and who have a different relationship.

Fulbright Arctic Scholars at the U.S. Department of State.

4. What are some important things you learned from your Arctic experience that are important for U.S. and non-U.S. citizen researchers to know?

Beth: One thing that I think every foreign researcher coming to the United States for the Initiative should take advantage of is geographical and institutional diversity, and flexibility. You can go anywhere in the U.S. that is relevant to your expertise and research, starting at any point during the Initiative’s timeframe (from 2021-2022). Having that freedom and support shouldn’t be taken for granted.

Greg: Even though this is the “Arctic Initiative,” it’s important to emphasize that critical research and work that can benefit Arctic communities isn’t just being done in Canada, Sweden, other northern areas, etc. This is a great opportunity to think outside the box in terms of your location, discipline, and focus. Counter-intuitively, it just might be that going to an institution in Hawaii to understand islanded or remote energy systems is what is most crucial for your research on energy transitions in Arctic and sub-Arctic regions.

Beth: It doesn’t have to be “New York, Los Angeles, Washington, D.C.” institutions. Local communities and other institutions around the country have something to offer, including in terms of learning about local cultures and attitudes.

Thinking of my own experience as an American researcher, I spent the majority of my time in Oulu and Utsjoki, Finland, but had the freedom to use my remaining time to go to Sweden, adding another perspective to my research, meeting with other like-minded researchers, and giving seminars and talks to local universities and organizations.

Greg: That’s an important point—take advantage of the academic and cultural value of your placement! I have to say that the connections I made locally were just as important as the scholarly connections. Meeting and knowing journalists, representatives from Indigenous organizations, local officials, museum curators, and ordinary citizens over a longer period allows you to build those relationships you wouldn’t have otherwise had.

Dr. Elizabeth Rink explaining her findings during the Fulbright Arctic Initiative II’s Research and Policy Findings at the Wilson Center in Washington, D.C.

Photo Credits: The Wilson Center.

5. What do you hope to accomplish with Cohort III of the Fulbright Arctic Initiative?

Beth: The product is a set of policy recommendations, or briefs, that can be used by the Arctic Council and politicians from around the world. In addition, each group is required to identify at least one other group project to work on that will be a deliverable by the end of the program, such as a group manuscript, a workshop, or some other kind of academic-policy-practice product.

Greg: I would say that the Fulbright Arctic Initiative is geared towards having real impact on the ground. In Cohort I, our policies were used to get funding from the Canadian government to develop a community energy planning toolkit under the auspices of the Arctic Council. For example, the connections that emerged from the Fulbright Arctic Initiative have led to a nearly $10 million Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Partnership Grant that involves Alaska, Canada, Norway, Sweden, and Finland, with 17 communities, as well as industry and utility partners. None of this would have been possible without the Fulbright Arctic Initiative.

We fully expect that the next round of scholars will be even more successful, as we draw and build upon the lessons of the first two rounds of the Fulbright Arctic Initiative.

Dr. Gregory Poelzer connecting with others at the Embassy of Finland’s Fulbright Arctic Initiative Reception.