From Boston to the Balkans: My Fulbright Global Scholar Award in Postwar Regions of the World

Laurie Lopez Charlés, Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist

2017-2018 Fulbright Global Scholar to Kosovo and Sri Lanka

As a 2017-2018 Fulbright Global Scholar, I am focused on the challenges of delivering family-focused mental health and psychosocial support in the post-conflict countries of Kosovo and Sri Lanka. I am a family therapist on my second Fulbright, and my current Global project is a culmination of many work visits to both Kosovo and Sri Lanka since 2010. The Fulbright Global Scholar award is a multi-country, trans-regional award, and my analysis explores how each country's state structures and international partnerships support (or subvert) strategies of scaling up mental health services for families.

Following are some reflections on my first segment of my award in Kosovo:

Mitrovice, Kosovo

During a visit to the Mitrovica bridge in early 2017, High Representative of the European Union (EU) for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini described it as “a symbol of the fractures, the wars and the pain marking the history of the Balkans in the last 25 years.” But, she added, the bridge can now be turned into “a symbol of dialogue, reconciliation, hope.”

This is what the Fulbright Global Scholar award is to me, as well--a chance to dialogue and to focus on postwar reconciliation and the hopes of families who survived. The Mitrovica bridge is quite plain and small, yet its complex symbolism is a perfect metaphor for my short time across this region of the Balkans. Mogherini, as High Representative of the EU Foreign Affairs, exemplifies one of the key regional partners that are so critical in post-conflict Kosovo.

In post-conflict states, during the transition from war to peace, many factors relevant to post-conflict reconstruction shape everyday family life in a country as much as they shape and are shaped by international/foreign policy leadership. The Mitrovice bridge symbolizes a division in the town, in the country, and in the region. It represents many things relevant to foreign policy, trade, and rule of law.

However, it is also, quite literally and simply, a bridge—citizens cross it daily and repeatedly—to get to their jobs, to buy bread or household goods, or to go to school or university. Such is the double life of families living in post-conflict states. The past and the present, war and post-war, compete constantly for your attention. I, too, find it challenging to remain cognizant of both states of mind.

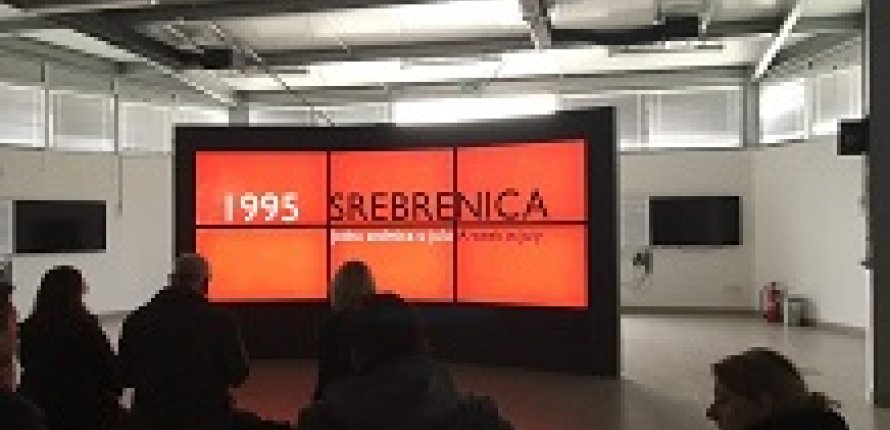

Srebrenica, Bosnia

I had been to Kosovo several times over the previous years as a consultant and trainer of family therapy, and I’ve spent many hours on Skype working with my colleagues in Pristina. But I’d never been to Mitrovice, where I ended up spending a lot of time, nor had I been anywhere else in the Balkans. My work in post-conflict countries has primarily taken me to other regions of the world outside of Europe. In my third week in Pristina, I decided to widen my scope of the region.

After working with my colleagues over several weeks in Kosovo, and encountering more questions about the war than answers, I decided to visit Srebrenica, Bosnia. The war in Kosovo is part of a complex Balkan history and one of several wars in the Balkans after the fall of Yugoslavia. Srebrenica, a neighbor to Pristina yet very hard to reach from Pristina, was important for me to visit. The memorial exhibits were powerful - the old Dutchbat Headquarters brought with it the deep grief and graphic shock I felt when I visited Auschwitz; the cemetery was reminiscent of Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia.

My colleagues in the Balkans, some of whom have managed to come to Srebenica, are a mixture of Albanians, Bosnians, Kosovars, and Serbians. Going to Srebrenica, and then talking about it with others in the region, was an opportunity for me to learn more about what citizens of the Balkans think of what has happened since the wars. For one man, a survivor of the Srebrenica death march, Srebrenica is his home—he will never leave it, no matter the ongoing divisions. I admired that. For another, a survivor of the siege of Sarajavo, it’s a sad, desolate, place that gives him a headache. I respected him so much for his honesty. For another, Srebrenica is an important place to bring people, to remember, and for her to talk about with outsiders. As one of the outsiders, I felt honored to be in her company. Yet another, a Bosnian, only in her 20s, told me she has come three times here, because, she says, it’s a duty to come, as citizens. I thought that was amazing. I felt as if it was my duty, too.

"The best way to shape the future is to work in the direction of the future"

-Claudio Grossman

Pristina, Kosovo

Back in Pristina, it was time to focus on the future. Along with my program partners from the Kosovo Association for Family Therapy, University of Mitrovice, and the University Clinical Center/Pristina, we held a roundtable discussion at a local hotel, themed “Trauma and Family: Strengthening Systems Across Communities After War.” The participants, from more than a dozen local NGOs and International Organizations, challenged all of us to think about the future - in balance with and alongside the past - for families in Kosovo and across the Balkans. I noticed that young people in the roundtable, in particular, seemed frustrated with the pace of change. They have the least to lose by speaking out, and, at the same time, have such potential for the return of all investments made in their country’s future.

The outcome of this important meeting was key: A group of us formed a committee to plan a conference on the roundtable theme in Spring 2018, coinciding with my second segment of the Fulbright Global Scholar award.